…have peritonsillar abscesses. This means they have an infection in their throat that causes pus to collect (abscess) around (“peri”) their tonsil. Usually the abscess occurs on only one side but rarely patients can have bilateral abscesses (I’m glad to say I’ve never seen it).

A peritonsillar abscess (PTA) is a complication of more common throat infections like strep throat or other bacterial causes of tonsillitis. What happens is the infection in the tonsil spreads into the adjacent tissue and forms pus that collects between the tonsil and the surrounding tissue. PTAs are most common in teens and young adults, especially around college age.

In these patients, there are several classic complaints and symptoms. First of all, patients with PTAs are miserable and look obviously sick when I first lay eyes on them. They complain of severe throat pain and ear pain (on the side of the abscess), as well as difficulty swallowing.

When they speak, their voices sound muffled- this is classically described as “hot potato voice,” similar to what your voice would sound like if you had piping hot potato in your mouth and tried to talk.

Patients will also complain that it hurts to open their mouths and they cannot open them fully (this is called trismus). Trismus happens because the inflammation from the abscess irritates the pterygoid muscles which help open the jaw and mouth.

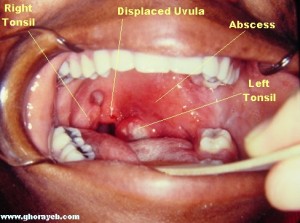

When I look in patients’ mouths, I’ll usually see bulging and redness of the soft palate as well as deviation of the uvula to the opposite side away from the abscess. The tonsils themselves are usually inflamed and red due to the infection and they may or may not show visible pus.

The key to the diagnosis is the appearance of the palate and uvula, as well as the presence of trismus. The appearance of the tonsils (swollen, covered with pus, red, etc) is irrelevant to the diagnosis of peritonsillar abscess.

How do I treat PTAs? The key is getting the pus out and getting patients on antibiotics. The three options for draining the pus are

1. Needle aspiration (draws the pus out into a syringe)

2. Incision and drainage (make an incision over the abscess and open widely to drain the pus).

3. Tonsillectomy

Options 1 and 2 can be done in the office in a cooperative patient, option 3 requires anesthesia and surgery.

Here’s where it gets tricky: not every patient has a true abscess. In my experience, the majority of patients with symptoms less than 48 hours do not have any pus collection, they just have infection and swelling of the tissues around the tonsil. If symptoms have been present longer than 48 hours, there is usually a lot of pus that has collected.

For this reason, I always start by attempting to find pus with a needle and syringe. Frequently, I will put the needle in and advance it in several different angles through the swollen peritonsillar area and get no pus out.

For patients who do not have a pus collection, I will prescribe antibiotics/steroids and they usually get better over the next couple days. Occasionally, pus will still form and need to be drained later- if this occurs, the patient will not get better and usually will feel even worse the second time I see them.

For patients who I do get pus out with the needle, the question at that point is whether to then proceed with incision and drainage to widely open the abscess cavity. In my residency, we typically just needle drained all of the abscesses- this is the way I was taught by my seniors and I never questioned it.

My experience since leaving residency and starting practice is that needle drainage fails frequently and requires an additional drainage before the problem is solved. I’ve recently started doing incision and drainage for all patients in whom I find a pus collection with the needle.

Scientific research over the years has shown that both needle aspiration and incision with drainage are effective at treating peritonsillar abscesses.

This study compared patients who had needle aspiration alone with patients who had incision and drainage. Needle aspiration was (eventually) effective but the majority of patients required more than 1 needle aspiration before the abscess had gone away completely.

This study had a group of 52 patients who all had needle aspiration (with pus drawn out). After that, half the patients had nothing else done and the other half had incision and drainage. Both groups did equally well (>90% had no recurrence of the abscess).

So, the evidence is conflicting. My experience since finishing residency has been more in line with the first study than the second.

After patients recover from their infection, I generally recommend that they schedule tonsillectomy which essentially eliminates their risk for ever getting another peritonsillar abscess.